JAN 2026: El Mirador, Engineering the Swamp (part 2 of 3)

Today the Mirador Basin is so sparsely inhabited that it is virtually uninhabited. Yet at its peak around 300 BC, it supported a regional population approaching 1,000,000. The city of El Mirador alone covered about 14 square miles, which is three times larger than downtown Los Angeles, with a population estimated at around 200,000.

What was it that allowed this ancient area to flourish and support populations unimaginable today?

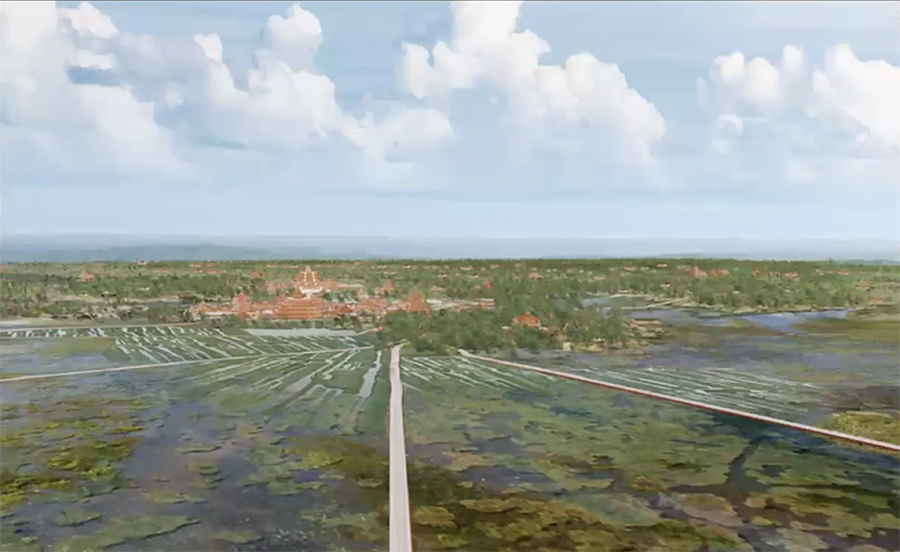

Richard Hansen, head of the Mirador Basin Project, believes there were several factors involved, most importantly, the development of a method of intensive agriculture known as chinampas, where rich muck from the swamps was used to create floating islands interwoven with canals. This allowed for high density, renewable agriculture. These farming practices evolved very early because the fertile muck of the swamp was what originally drew people to this area.

Topographical map showing swamps (blue) & raised outcroppings

From "The Cultural and Natural Legacy in the Cradle of Maya Civilization: New Perspectives. YouTube Lecture: Dr Richard Hansen. Used under Creative Commons CC BY license

It is estimated that over 64% of the Mirador Basin in the Pre-Classic period consisted of perennial wetlands or shallow lakes. The first evidence of farming in the Basin dates from the Middle PreClassic (1000 BC to 600 BC), when seasonal crops were planted in areas of receding water during the dry season.

Chinampas Agriculture

From "The Cultural and Natural Legacy in the Cradle of Maya Civilization: New Perspectives. YouTube Lecture: Dr Richard Hansen. Used under Creative Commons CC BY license

As the population expanded, the Maya began a massive geo-engineering project to modify the wetlands (600 BC to 300 BC). This corresponds to the transition from the Middle to Late PreClassic period, when canals were dredged and chinampas — semi-floating agricultural platforms — were constructed and extended far out into the bajos surrounding the city. The waterlilies growing in the canals (see right of photo) came to represent this type of farming.

The traditional title for Maya royalty was "People of the Waterlily"

Stela 1, Bonampak, Mexico. Photo by B. McKenzie

For the next thousand years, Maya royalty referred to themselves as "People of the Waterlily," often symbolized by a fish nibbling a waterlily as seen here in an absurdly wonderful headdress from Bonampak circa 792 AD., nearly 1000 years later. It is interesting that Bonampak was a river city and did not engage in this type of bajo farming, but they did retain the symbols and mythology from the cradle of their ancient past.

Chinampas farms extended far into the bajos surrounding El Mirador

From "The Cultural and Natural Legacy in the Cradle of Maya Civilization: New Perspectives. YouTube Lecture: Dr Richard Hansen. Used under Creative Commons CC BY license

This first agricultural revolution and the prosperity it brought enabled a second revolution, where almost all of the city not occupied by architecture and public plazas was terraced. Rich muck from the swamps was transported, by the thousands of tons, to these terrace gardens.

Pollen samples from cores taken from nearby lakes reveal that at this time the Maya were growing corn, beans, squash, cotton, cacao and palms (for thatching material as well as oil) all over the city center. Because of the richness of the swamp bottom-material, these gardens retained their fertility for over a thousand years even when the same crops were grown again and again in the same spot, year after year. The "Archipelago City" was transformed into a "Garden City", the entire urban area covered with terraces and residential compounds producing an immense abundance of food.

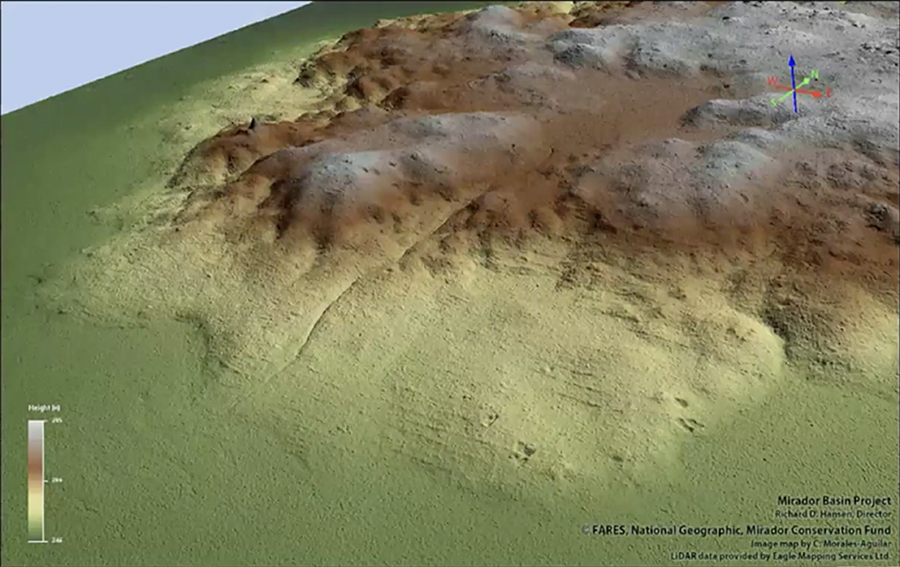

LiDAR verifies the magnitude of the agricultural terrace system

From "The Cultural and Natural Legacy in the Cradle of Maya Civilization: New Perspectives. YouTube Lecture: Dr Richard Hansen. Used under Creative Commons CC BY license

We can see from LiDAR that all available land not paved over by architecture was terraced. The amount of labor it took to construct the hundreds of kilometers of terrace walls and carry the thousands of tons of swamp mud to fill the terraces and enrich these new farming areas is staggering. The combination of chinampas and the terraced gardens was amazingly productive, producing the riches and supporting the population densities needed to construct the gigantic pyramids and public works, and to exert political and ideological control over the entire Basin.

LiDAR also identified animal corrals (unfortunately not visible in this image), which indicate an almost industrial scale of animal production. Investigations on the ground found evidence that turtles and dogs were being raised for food in these pens. Other evidence points to significant amount of turkey also being consumed in the city at this time.

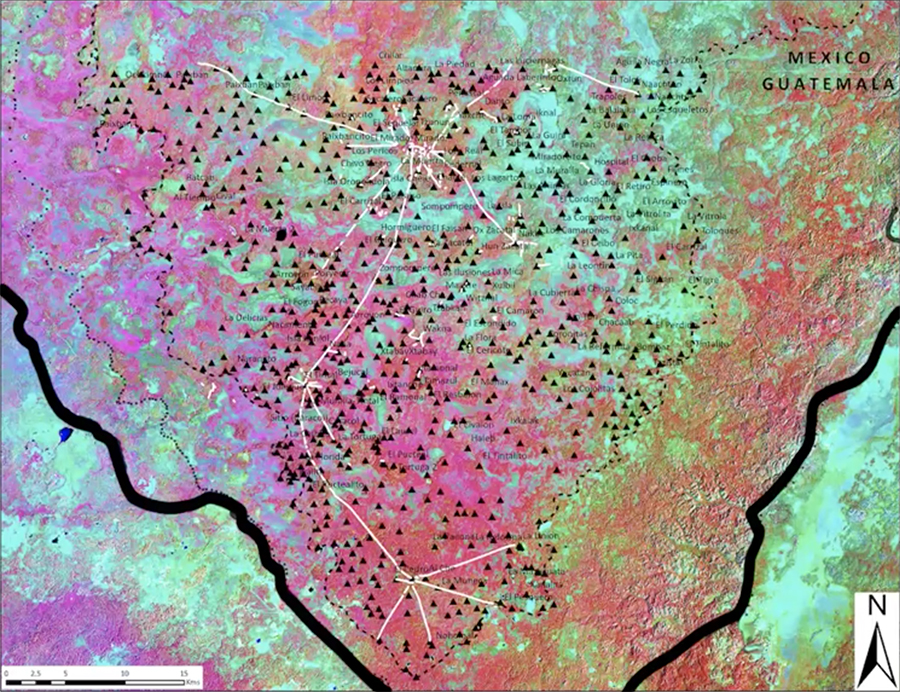

Sacbé-ob supported ceremonial processions within the city as well as far-flung regional commerce

From "The Cultural and Natural Legacy in the Cradle of Maya Civilization: New Perspectives. YouTube Lecture: Dr Richard Hansen. Used under Creative Commons CC BY license

Navigating a swampy area with uneven outcroppings requires a system of elevated roads. These roads were called sacbé (meaning "white road") because they were surfaced with waterproof white stucco, similar to that used for the plastered elevated plazas at the base of the great pyramids in the interior of the city.

It is thought that these ceremonial white roads were originally extensions of the urban stucco plazas, where causeways were built to interconnect the ceremonial areas with residential and commercial parts of the city. These causeways eventually expanded into the network of raised highways that eventually connected the major cities of the Basin.

Richard Hansen even speculates that, because of their whiteness, these roads would be brightly illuminated by reflected moonlight. This enabled traders, who by necessity carried all their goods on their backs (there were no beasts of burden), to travel by night and avoid the fierce heat of the tropical sun.

El Mirador, as central node of the sacbé system, was the nerve center of the Mirador Basin

From "The Cultural and Natural Legacy in the Cradle of Maya Civilization: New Perspectives. YouTube Lecture: Dr Richard Hansen. Used under Creative Commons CC BY license

This map shows the density of cities in the Pre-Classic Basin. A network of highways served to consolidate the Mirador Basin into what appears to have been the first political state in the Americas, with El Mirador at the center.

Although this region was rich in agricultural products, there were necessities and luxuries that demanded long distance trade. For example, the Maya were a stone age people without iron tools, so they depended on obsidian blades for cutting tools and ceremonial objects. Obsidian was imported from volcanic highland Guatemala, a distance of over 200 miles. Likewise, salt, essential for survival in hot tropical climates, was imported from the solar evaporation works along the Belize coast. In the case of salt, it appears that it was transported by canoe upstream along rivers as far as possible, then carried overland by foot for the last leg of the journey.

There is also evidence that large quantities of imported Strombus (conch) shell served as an early form of money, and was imported from the coasts. The difficulty of obtaining conch by overland trade served to increase its value the farther it travelled from its source. Then there was jade, the ultimate prestige good, sourced from the far Motagua River Valley in Honduras.

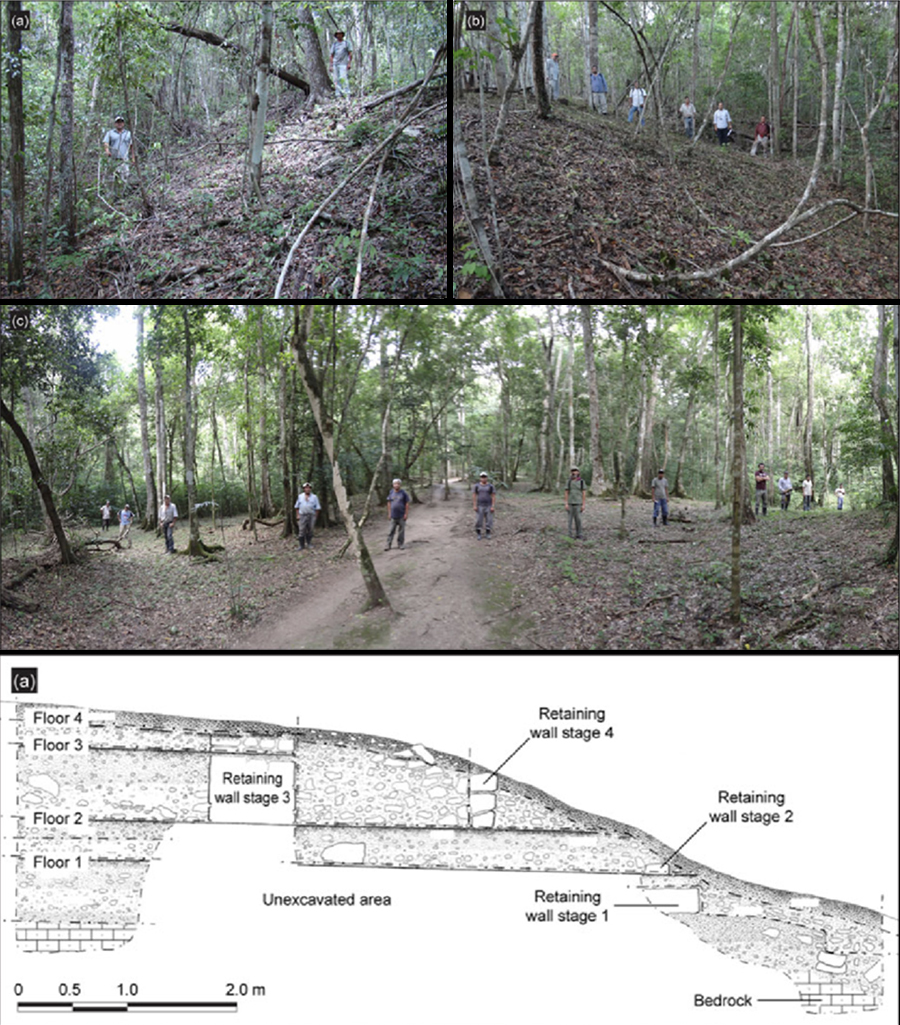

Sacbé-ob were massive. The middle photo shows a Sacbé eqivalent to a 12 lane modern highway

From "The Cultural and Natural Legacy in the Cradle of Maya Civilization: New Perspectives. YouTube Lecture: Dr Richard Hansen. Used under Creative Commons CC BY license

The scale of the raised causeway system, like everything else in El Mirador, was massive. We read that the roadways were raised above the surrounding landscape by between 6 and 20 feet, and that they were 131 feet wide, which is the equivalent an eleven-lane modern highway, assuming that the average width of a highway lane is 12 feet.

These elevated roads were built over several centuries. Combined with an advanced water management system which we will discuss next, they supercharged El Mirador's agricultural systems, making the city a dominant economic (and political) power in the region.

Art, technology, and foundational mythology were fused in this ancient water catchment system

A water-catchment system built on the side of an internal sacbé. Photo courtesy of Jeff Purcell

This water-catchment system, located in the run-off zone between a large pyramid and the elevated Calzada Danta Sacbé, was being explored by Craig Argyle when he uncovered the Popol Vuh panels, dated from 300 BC. Argyle's YouTube video tour of this ancient water catchment system and the Popol View panels gives a wonderful sense of this ancient water management system that can't be conveyed by photos alone. Please take a moment to enjoy this short video.

Decorated water collection & reservoir system on an inner city causeway, circa 300 to 200 BC

The foam rubber was placed by archaeologists to protect an area where additional artwork was being uncovered. Photo courtesy of Jeff Purcell

Even though El Mirador was located in the middle of a tropical swamp, a water management and reservoir system was required to both channel flood waters during the rainy season as well as to provide fresh water for drinking and other purposes during the dry months.

The sophisticated sluice and pool systems of these catchment areas and reservoirs was enhanced with finely modeled stucco decorations just above the water line. Depicting nearly the entire pantheon of Maya cosmology, these decorations include several variant images of Itzamná in avian form, an undulating feathered serpent with aquatic references, aquatic elements, repeated images of the rain deity Chak, and what appears to be the Hero Twins of the Popol Vuh, with one transporting a decapitated head. Such rich iconographic details, lining the walls of a utilitarian reservoir, testifies to a sophisticated culture that could easily fuse technology with theology.

Itzamna and his incarnation as Principal Bird Deity appear in the coils of a giant serpent

Photo courtesy of Jeff Purcell

In the murky and often poorly understood Maya mythologic pantheon, the Principal Bird Deity (often referred to by scholars as Itzam Yeh, or affectionately as the PBD) is sometimes seen as the avian avatar of the supreme creator god, Itzamna. He is frequently depicted perched atop the World Tree, while Itzamna himself is seen as the tree itself. In classic art, Itzamna often wears the Principal Bird Deity as a headdress.

However, in the Popol Vuh, Seven Macaw (Vucub Caquix, who shares the same bird iconography) is the vainglorious jeweled bird who poses as the "False Sun" and who the Hero Twins must shoot with their blowguns in order for the true sun to appear and creation to take place.

Hansen remarks that, curiously, the bird (photo on right) appears to be feeding the fish, while in classical art, he is eating the fish -- a detail that no one seems to understand. For comparison with a "fish eater", see the beautifully dynamic sculpture from the Copán Sculpture Museum (circa. 628—690 AD) showing the waterbird worn as the headdress of the Rain God Chac.

In the San Bartolo mural, you can see this deity on the West Wall, where the bird sits atop the directional trees.

Hunahpu, one of the Hero Twins, rescuing the severed head of his father, the Maize God

Photo courtesy of Jeff Purcell

This panel, known as the Popol Vuh Panel, was named after a Kiche Maya text written down after the Spanish Conquest in the seventeenth century. Until the discovery of PreClassic panels like this, it was suspected that the Maya creation stories in the Popol Vuh had been distorted by the heavy hand of Spanish friars, but the discovery of this panel demonstrated the antiquity and authenticity of the Popol Vuh story, existing over a thousand years before the colonial-era recording of it.

Hun Hunahpu, father of the Hero Twins, was decapitated after being challenged to a ballgame by the Lords of the Underworld. His sons, Hunahpu and Xbalanque, are pictured here swimming in the underworld of Xibalba as they rescue their father's decapitated head. Hunahpu (shown here) wears a yoke around his waist, marking him as a ballplayer. He carries his father's head on his rump, which is shown trailing a blood scroll and has a Spondylus shell, used to mark the dead, over his mouth. Hun Hunahpu will later be resurrected and become the Maize God, while the Hero Twins will ascend the heavens to become the Sun and the Jaguar Sun at Night.

At least seven ballcourts have been found at El Mirador, and they are present everywhere in the Basin. The ballcourt, always aligned North/South so the ball bouncing off the ballcourt sides reflects the daily journey of the sun, was to the Maya a portal to the underworld, and had profound religious, political and military significance.

For more on the intricate Maya creation myth, see Patricia Amlin's much-honored Popol Vuh: The Creation Myth of the Maya, an animated film which employs authentic imagery from ancient Maya ceramics and the voice of native Yakama storyteller, Larry George.

A contemporaneous portrait of Hero Twin, Hunahpu, from the nearby site of San Bartolo

From "Murals and Mysteries of the Maya. YouTube Lecture: William Saturno. Museum of Science, Jan 21, 2015.

This contemporary mural from the nearby site of San Bartolo features Hunahpu as he performs four sacrifices to the trees of the cardinal directions at the creation of the universe. Hunahpu also sacrifices his own blood to make way for the investiture of the shaman-kings who were to govern the Maya people from that time forward.

William Saturno, whose discovered the San Bartolo murals, has a wonderful lecture "Murals and Mysteries of the Maya" where he discusses early kingship and investiture and the role of calendrics and astronomy in the timing of rituals which re-enact events of the deep mythological past. Central to his argument is that the art and architecture of the Pre-Classic was in no way inferior to what came later, that the mythology and ideals of divine kingship was adopted wholesale by the later Classic Maya, and that even today much PreClassic mythology remains current among the Maya people.

Note: At the beginning of his lecture, Saturno presents a larger-than-life portrait of his mentor, Ian Graham, the first archaologist to visit and map El Mirador in 1962. Saturno's lecture is as illuminating as it is enjoyable.

Richard Hansen: "Discovering the panels were like discovering the Mona Lisa in a sewer"

Photo courtesy of Jeff Purcell. The pieces of foam rubber at the bottom are temporary protection put there by the archaeologists to protect the unexcavated lower level while additional decorated steps were being uncovered.

Hansen sees no evidence that the massive temples, roadways and water control systems were built by slave labor. Instead, he thinks a "labor tax" was imposed on each family group to provide the manpower for these massive constructions.

Most interestingly, Hansen believes that this drive to make their myths concrete was what compelled the Maya to master the technologies required to support the population densities needed to build such places.

Water management and the network of causeways amplified the agricultural riches of El Mirador

Photo courtesy of Jeff Purcell

The decorated reservoirs anchored the city's water requirements in myth. And El Mirador's vast network of causeways did more than facilitate trade; it circulated the myths, rituals, and shared culture that bound the Basin cities together, consolidating them into what appears to be the first true political state of the Americas.

While complex social organization based on divine kingship enabled the marshalling of labor and logistics needed to build this city, Dr. Hansen argues that it was their mythology that provided the will and impetus to manifest their origin stories in stone. Ultimately, it was these architectural forms and concepts of urban design, grounded in myth and mirroring their cyclic sense of time and the cosmos, that survived El Mirador and became the sacred blueprint for Maya civilization for the next thousand years.

Our February 2026 issue, "The Fall, the Legacy", will examine why El Mirador collapsed, and how its legacy continued to shape the Classic Maya who came after. Expect it in your mailbox on the first Sunday of the month, February 1, 2026.

We welcome questions, comments, photos, travel stories, & other musings, and will share selected contributions in the February 2026 Newsletter.